A six-story tall statue of Robert E. Lee overlooks Richmond, the capital of Virginia. Unlike other statues of Confederate figures that once lined Monument Avenue, the Lee statue stands on state property. Virginia’s governor, Ralph Northam, announced in June that he would order the statue removed. Richmond’s mayor, Levar Stoney, agreed with the decision, remarking that “Richmond is no longer the capital of the Confederacy.”

Northam’s decision is consistent with a nationwide response to protests against systemic racism. After the death of George Floyd, Mayor Stoney ordered the removal of several confederate statues on Monument Avenue. Confederate statutes have been removed — by official action or by protestors — from Charleston, Norfolk, Alexandria, Louisville, Jacksonville, Mobile, and other cities.

Northam’s order to remove the statue has nevertheless been challenged in a lawsuit filed by William C. Gregory. The Virginia resident claims to be a descendant of two landowners who deeded the property to the state on which the statue stands. He contends that removing the monument would breach the state’s promise to his ancestors to “faithfully guard” and “affectionately protect” the statue.

What Do Confederate Monuments Commemorate?

Exactly what the monuments commemorate is a subject of debate. To those who view the Civil War as a war of northern aggression rather than the Union’s use of necessary force to preserve constitutional government, the monuments are part of southern heritage. The Daughters of the Confederacy argues that Confederate monuments “honor the memory” of “fallen forebears.”

To many others, the monuments honor traitors who tore the country apart in order to preserve the institution of slavery. Annette Gordon Reed, a professor of legal history at Harvard Law School, told an interviewer that thousands of members of the Armed Forces, black and white, gave their lives to overcome the Confederate rebellion. She believes “it dishonors them to celebrate the men who killed them and tried to kill off the American nation.”

The removal of monuments in seven former Confederate states has been hampered by laws that limit or prevent local governments from displacing them. Governor Northam’s pledge to remove the Lee statue from state property in Richmond has been challenged by a lawsuit that is making its way through state courts.

Gregory’s Lawsuit

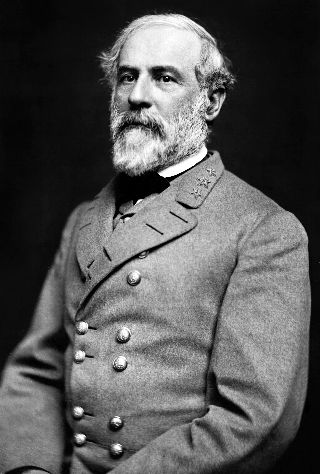

The Lee monument was created by a popular French sculptor and appears on the National Register of Historic Places. As the state explains however, at least in Virginia, a Register listing “results in no special protection or requirements on what a property owner may do with a property.”

Gregory’s lawsuit contends that the circular plot on land on which the monument stands was deeded to the Lee Monument Association in 1887. The Association erected the monument and deeded the land to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1890. The deed was signed by the governor pursuant to a joint resolution of the general assembly.

The deed states that the commonwealth accepted the gift with the guarantee that it would hold the statue, pedestal, and circle of ground “perpetually sacred to the Monumental purpose to which they have been devoted and that she will faithfully guard it and affectionately protect it.”

The lawsuit alleges that Gregory’s ancestors signed the deed on behalf of the Lee Monument Association. The lawsuit claims that Gregory would be irreparably harmed if the monument were removed, apparently because he takes pride in his family’s connection to the monument.

Historian Testifies as Expert Witness

Descendants of Virginia slaves might just as easily argue that they are irreparably harmed by the existence of a “sacred” monument to a Confederate general who fought to preserve the institution of slavery. To put the monument in its historical context, the state called historian Edward Ayers as an expert witness.

Ayers testified that the drive to fill public spaces with Confederate statues was designed to rehabilitate the image of the Confederacy. Ayers noted that the monuments were erected during an era when white politicians in the South were taking action to stifle the political power of African Americans.

Ayers expressed the belief that the Lee monument is not just a tribute to Lee. By its very size and dominance of a public space, the monument sends a message about the legitimacy of the Confederate cause. Ayers testified that the monument portrays Lee as “a great man” who fought for a just cause — “a new nation based on slavery.”

The court is unlikely to pass upon the political wisdom of maintaining monuments to leaders of an insurrection. The two competing legal issues that the judge must confront are whether Gregory’s family connection to a member of the group that deeded the statue allows him to challenge the monument’s removal, and whether the governor has the power to order the statue’s removal without the legislature’s consent. The judge will likely make that decision in the near future.

Update: In an August 3, 2020 decision, the court dismissed the lawsuit and ended the temporary injunction that prevented the monument’s removal.

Photo via Good Free Photos